French, 1943

Original text

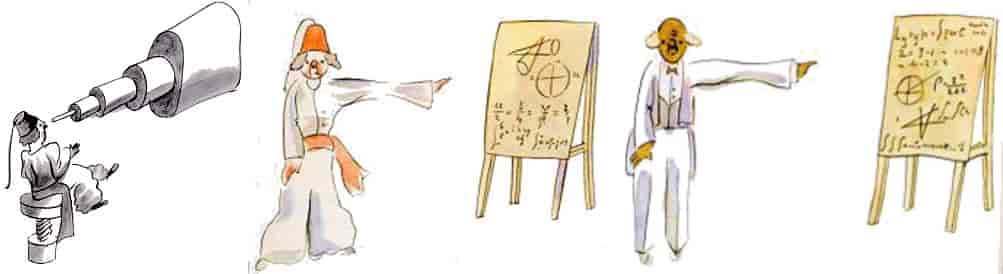

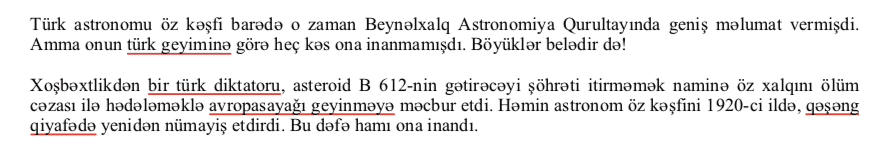

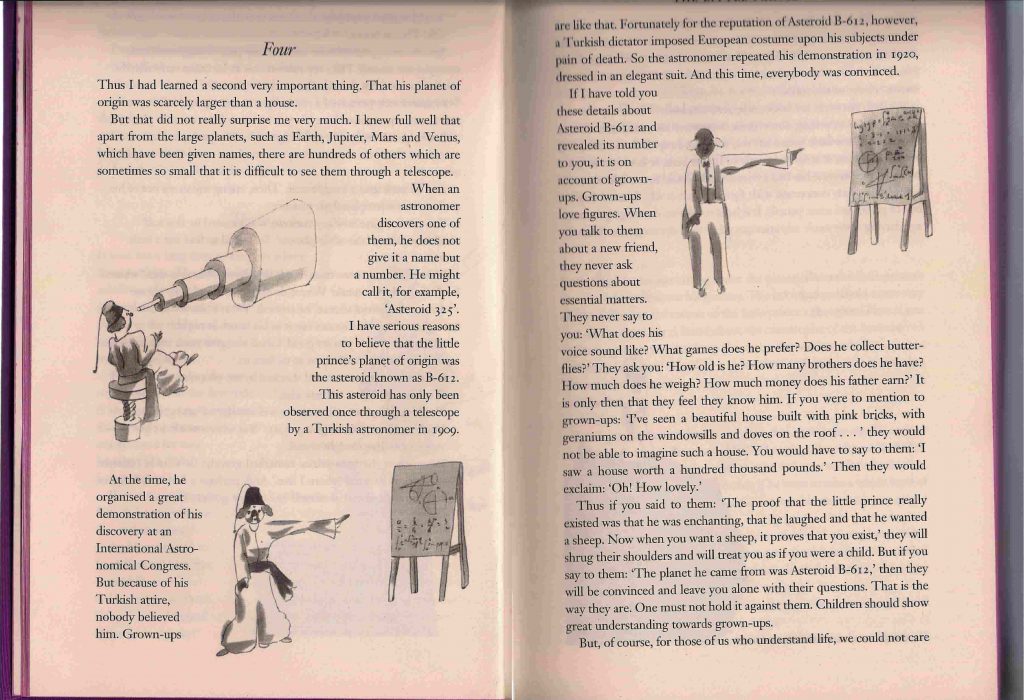

Cet astéroïde n’a été aperçu qu’une fois au télescope, en 1909, par un astronome turc. Il avait fait alors une grande démonstration de sa découverte à un Congrès International d’Astronomie. Mais personne ne l’avait cru à cause de son costume. Les grandes personnes sont comme ça. Heureusement pour la réputation de l’astéroïde B 612 un dictateur turc imposa à son peuple, sous peine de mort, de s’habiller à l’Européenne. L’astronome refit sa démonstration en 1920, dans un habit très élégant. Et cette fois-ci tout le monde fut de son avis.