claiming The North

A Mapping Project and Database on the Legacy of Geographical Name Changes in the Rize kaza throughout the 1910s

- Introduction

- Sources & the Database

- The Selection Process: Which places were to be renamed?

- Remaking the Landscape: How did the Rize Committee decide on the new names?

- The Legacy: To what extent did the place-name changes last?

- See Also: Glossary, Bibliography and Additional Sources

Introduction

In this post, I will be looking at the geographical Turkification process carried out by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) in the Rize kaza on the southern Black Sea littoral of the Ottoman Empire between 1914 and 1916. I will discuss the changes in terms of a) the selection process of which places would be renamed; b) the criterion (and the lack of) for picking out the new Turkish names; c) and the impact that the Russian Occupation of Rize (1916-1918) had on the renaming process.

Historical Background

In the early days of 1913, the Thessaloniki-based CUP organized a coup d’état and overthrew the Ottoman government. The CUP ousted the members of the Sublime Porte and thus began the reign of the triumvirate made up of three pashas: Enver Pasha, Talaat Pasha and Ahmet Jamal Pasha. Following CUP principles, the three pashas aimed to promote Turkish nationalism among Muslim Anatolians who they believed would be brought together by a shared sense of religious brotherhood. They also took the initiative to implement a series of Turkification policies. One of the most well-known of these policies was the Turkification of place-names throughout the Empire. Within three years of ascending to power, the triumvirate’s Enver Pasha issued an edict exactly for this purpose.1

Hover Over the Text for the Transliterated Turkish

“It has been decided that provinces, districts, towns, villages, mountains, and rivers, which are named in languages belonging to non-Muslim nations such as Armenian, Greek or Bulgarian, will be renamed into Turkish. In order to benefit from this suitable moment, this aim should be achieved in due course.”

6 January 1916 - Enver Pasha

“Memalik-i Osmaniyye'de Ermenice, Rumca ve Bulgarca, hasılı İslam olmayan milletler lisanıyla yad edilen vilayet, sancak, kasaba, köy, dağ, nehir, ilah. bilcümle isimlerin Türkçeye tahvili mukarrerdir. Şu müsaid zamanımızdan süratle istifade edilerek bu maksadın fiile konması hususunda himmetinizi rica ederim.”

23 Kânun-u Evvel 1331 - Enver Paşa

Over two hundred places in Rize, too, were selected for the renaming process. However, exactly two months after Enver Pasha’s decree, the region was occupied by the Russian army during the Caucasus Campaign of the First World War and it remained under the Russian Empire’s rule until March 1918. By 1923, Rize was part of the newly founded Republic of Turkey. My project traces the names of Rize in the last century as it switched hands between two empires and a republic.

Sources & The Database

The primary source for this project is a set of Ottoman administrative records from 1914-1916 I found in the Directorate of State Archives of the Republic of Turkey.2

The primary source for this project is a set of Ottoman administrative records from 1914-1916 I found in the Directorate of State Archives of the Republic of Turkey.2

The records consisted of a paragraph briefly stating the purpose of this document and a three-column list of 222 place-names. The first column listed the official place-name; second, the proposed Turkish name; and third, the “reason for change”.

To create the database, I simply transferred the listings to an Excel document and translated the listed reasons for the change. I looked up the names in Tahir Sezen’s gargantuan tome called the Osmanlı Yer Adları (Place-Names in the Ottoman Empire, only available in Turkish) though it excluded smaller villages and neighbourhoods.3

Then, I georeferenced an administrative map of Rize from 1930 (also found in the State Archives) using QGIS to see if there were any matching place-names with my primary source.4

Then, I georeferenced an administrative map of Rize from 1930 (also found in the State Archives) using QGIS to see if there were any matching place-names with my primary source.4

After that started a three-day-long Googling marathon during which found countless web entries using the old and new names. These ranged from nostalgic poems posted on Facebook groups, Instagram and Twitter #hashtags, to names of cafes, stores and sports clubs persistently using the pre-1916 name.

Luckily for me, locals still actively use some of the older names. For example, searching for #atyonoz, the former name of Bozukkale and Incesırt districts, yields over a hundred correctly geotagged posts on Instagram.

Once I knew the current names of the places, I used Google Earth to add each one’s geographical coordinates.

Transliterating Ottoman script to Latin letters can get tricky very easily, especially considering most of the place-names were of Armenian, Greek, Georgian or Laz origin. I included any alternative spellings I encountered in the secondary sources. My project benefited greatly from renowned linguist Sevan Nişanyan’s collection of place-names in Thrace and Anatolia called the Index Anatolicus for alternative spellings as well as invaluable etymological information.

Additionally, I wanted the database to be inclusive of both official names and the unofficial, colloquial names that a place may be known by. I was able to find colloquial names in Armenian, Pontic Greek, Georgian and Laz for about a fifth of the place-names listed. For the Pontic Greek names, I used the records brought together by the Center of Asia Minor Studies (Κέντρο Μικρασιατικών Σπουδών) both in the Greek letters and the Latin alphabet.

Here is the link to my database if you’d like to take a look.

The Selection Process

There are not many primary sources that describe the inner workings of the renaming process that took place under Enver Pasha’s orders. Scholars tend to point out how the CUP allowed the Kurdish and Arabic place-names to remain unchanged to argue that the place-name changes did not have an impact on the Muslim communities.5 The statement of purpose that came accompanying the place-name change records in Rize can help us challenge that assumption.

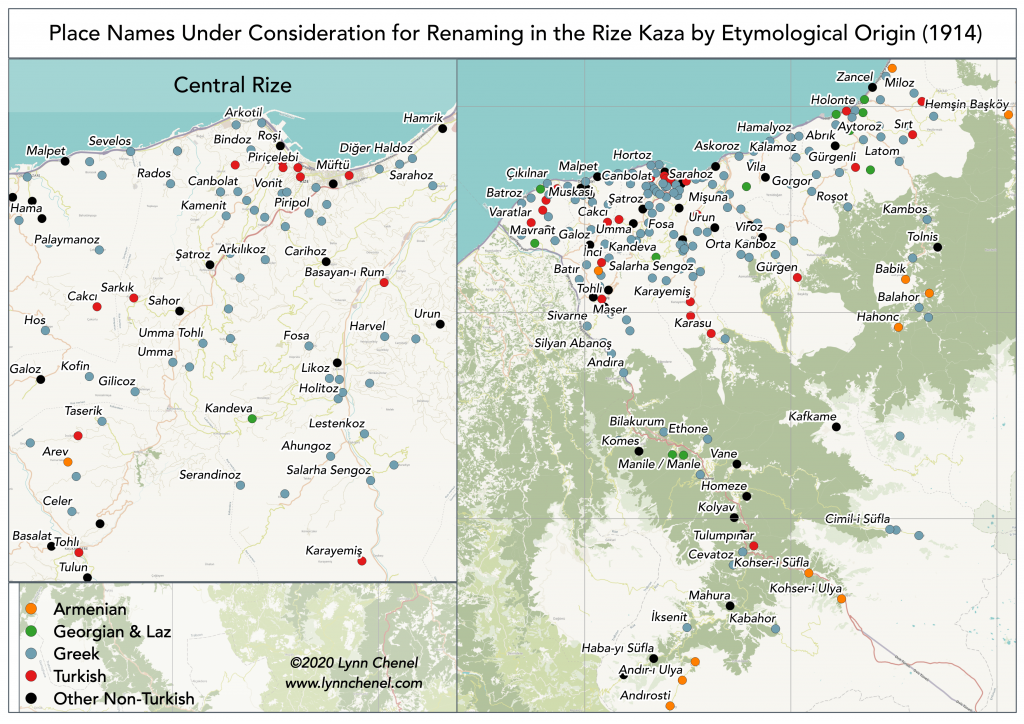

The paragraph informs us that these documents were prepared in Rize in 1914 and reported back to the Ottoman Capital. More importantly, it also tells us that a local committee gathered in Rize to “replace the non-Turkish names of villages and mahallahs ” in the districts of Central Rize, Kur’ai Seba, Karadere, and Mapavri (modern-day: Central Rize, Ikizdere, Kalkandere and Çayeli). The wording “non-Turkish” instead of the generally assumed “non-Muslim” is important here. Below are the graphs for the 222 locations the Rize Committee listed in their report.

The etymological origin of the place-names suggested for renaming:

As the graph shows, around 7% of place-names changed were in Laz or Georgian and %5 were in Armenian. It should not be overlooked that, by the twentieth-century, all the Laz and the great majority of Georgians under Ottoman rule had been practising Islam for over a century.

Additionally, most of the place-names in Armenian were settled and to this day populated by the Hemshin people who are an Armenian speaking (Western Armenian’s Homshetsi dialect) Muslim people. Hence not only non-Muslims but all linguistic minorities in the Rize kaza including Muslim Georgians, Laz and Hemshin peoples were impacted by the CUP’s Turkish name surge.

Remaking the Landscape

The Translation Question

On both sides of the spectrum, scholars suggested that the new place-names were either “translated equivalents” based on the original place-names’ meaning, or random words haphazardly assigned to non-Turkish-sounding as they were ordered from the top-down.6 By studying the Rize Committee’s report, we can argue that in Rize neither was entirely the case.

The Rize Committee listed their reasoning behind choosing the new place-names for 90% of the entries in their report. Not one of the reasons mentioned was concerned with translating the original place-name. Regardless, about 2% of the places did receive new names that were either direct translations or names that were somewhat inspired by the old ones. Some examples include:

The rivers of Kalopotam from the Greek Καλοποτάμι (the good river) and Makrabudam from Μακραποτάμι (the long river) were respectively translated as Iyidere and Uzundere protecting the originals’ meaning.

The village of Balahor from the Greek Παλιόχωριό literally “the old village” became the Yeniceköy meaning “the new village”.

The Haldoz quarter in Central Rize meant to “the one from Χαλδία”. The new name Bağdadlı refers to “the one from Baghdad”.

Explaining the Changes

The Rize Committee’s official reasons for the name changes can be organized into ten categories. To clarify, the Committee must have found some original names passable that seventeen of the listings were allowed to keep their name with no or minor changes in spelling. They were all Turkish-sounding names without exception. I excluded those from the following data.

The reasons why the new place-names were chosen by order of popularity:

A touristic signpost using the old Laz name Çeçeva alongside Laz inside jokes and puns.

The official name for Çeçeva is Haremtepe since 1916.

34% were named after a certain geographical or architectural feature in the village such as hills and bridges.

17% were named after a Turkish name the committee said that the village was readily known by.

12% were named after what the village is famous for such as raising teachers or growing certain fruits.

11% were named after the main source of income for the majority of the village residents; such as the Fishermen’s Village.

10% were renamed without any given reason.

8% were named after the name of somewhere already existing in the village. E.g.: if the village had a spot called Sunnyhill, the village was renamed Sunnyhill.

4% were named after someone who is not from the village but has visited or done charity there.

2% were named after what the village “seemed like” some of these included: large, small, and a farm.

1% had their former name shortened.

1% were renamed according to its residents’ wishes.

The etymological origin of the place-names that were initially suggested for renaming but later exempted:

The 1916 Vision

On the one hand, the fact that the Rize committee existed tells us that there was at least some level of local involvement in the renaming process. The analysis shows us that there is one case where the Rize Committee paid heed to the local people by renaming the village according to their request. Moreover, it can be argued that the Committee took local history and culture into consideration by naming certain villages after their reputed products and people.

On the other hand, the common reasons listed shows that some of these new names were in fact arbitrarily given without any explanation. Furthermore, the most recurring element found in the new place-names was geographical features. Upon inspection, it is clear that some of these names were presumptuous guesses and they showed.

For instance, the creek called “lake” is a very telling example: The Hemshin settlement of Kabahor was renamed Gölyayla, literally the “lake-plateau”. Needless to say, there is not one lake on the entire plateau but a creek which was renamed to “Göl” (lake) around the same time.

More strikingly, twelve of the new place-names had the word -hill attached. Those villages were likely hilly indeed, but in Rize, one has to ask which place is not?

The very name of the city, Rize, comes from the Greek plural noun Ριζά (Riza) meaning the ‘the roots of a mountain’ or ‘the foot of a mountain’ as in ριζοβούνι (rizovouni; vouno translating to the mountain). Considering the geography in question, the achievement would be to find a village on level terrain and name it “Flatland”.

Overall, neither careful translation nor arbitrary assignment can describe the renaming process that took place in Rize in 1916; certainly, there were exceptions. Nonetheless, the data clearly illustrates that the majority of the new place names were picked out as if from a deck of cards featuring generic geographical attributes, sources of income, consumables, rich people, and a wildcard called “any-name-goes”.

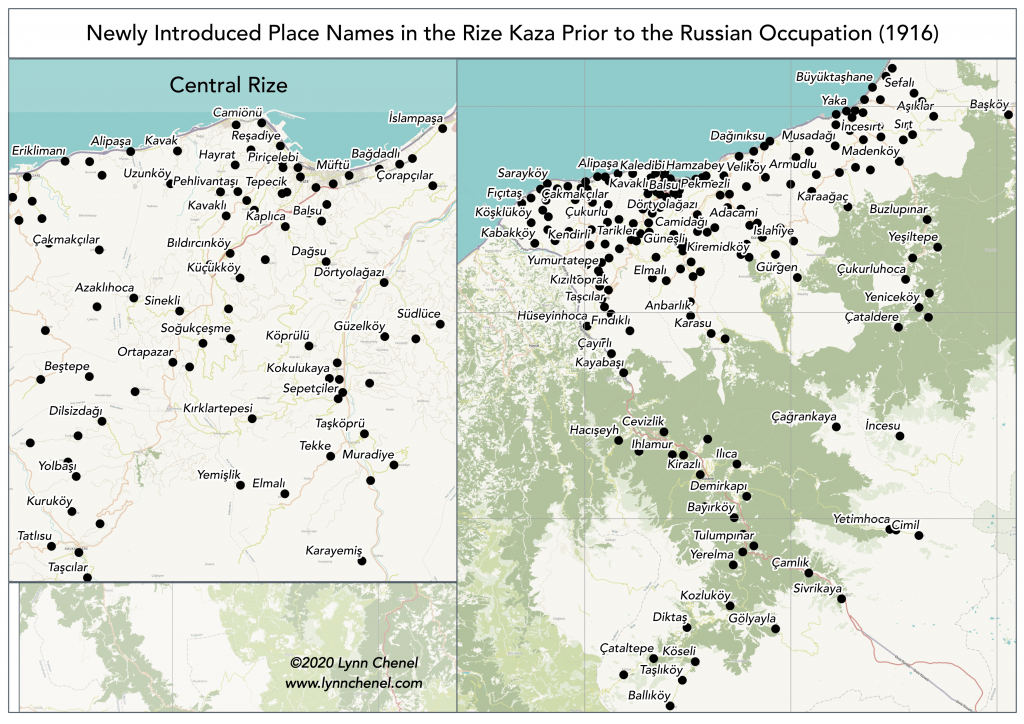

The Legacy

In Rize, the CUP’s Turkish name surge was abruptly interrupted when the region went under Russian control in 1916 and remained so for the next two years. There is not enough evidence to say whether the renaming process was done in Rize by the time the Russian army arrived; though it probably was the case because the georeferenced administrative map of Rize from 1930 was labelled with the CUP-given names.

Today, 93% of the places renamed in Rize between 1914 and 1916 still carry their CUP-assigned names. The remaining 7% also have Turkish names, though different. Even though the old names are widely known among locals and often used colloquially, none have officially gone back to their pre-1914 names.

Also See

Glossary

Kaza: [قضاء] an administrative division historically used in the Ottoman Empire, comparable to a district or subdistrict.

Pasha: [پاشا] one of the higher ranks in the Ottoman and Turkish political and military system. Turkish: Paşa.

Mahallah: [محلة] a neighborhood, quarter or district. Turkish: Mahalle.

Sources

1. Enver Pasha’s letter: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Devlet Arşivleri, Cumhuriyet Arşivi. 000955, 23 Kânunuevvel 1331 (5 Ocak 1916). [State Archives of the Republic of Turkey, Republican segment, 000955, 23 Kânunuevvel 1331 (January 6, 1916).]

2. Rize Committee’s report: DH.ID., 97-2/25-2. State Archives of the Republic of Turkey.

3. Tahir Sezen. Osmanlı Yer Adları [Place-Names in the Ottoman Empire] (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Başbakanlik Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü Yayin: Ankara, 2017).

4. The Rize Map Georeferenced: Rize B_13 (1930). Harita Umum Müdürlüğü [The General Directorate of Maps]. State Archives of the Republic of Turkey.

5. Lusine Sahakyan. Turkification of the Toponyms in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey (Arod: Montreal, 2010)., pp. 13-14.

6. Translation argument: Nurdan Kavaklı. “Novus Ortus: the Awakening of Laz Language in Turkey” Idil 4:16 (2015)., p. 137. Arbitrary assignment argument: Sevan Nişanyan. Adını unutan ülke: Türkiye’de adı değiştirilen yerler sözlüğü [The Country that Forgot Its Name: A Dictionary of Place Names Changed in Turkey] (Everest: Istanbul, 2010)., pp. 51-53.]

Helpful Links

Index Anatolicus: A project aiming to record all current and historic place names within the borders of Turkey and adjoining former Ottoman lands.

A collection of Laz and Hemshin place-names in the southeastern Black Sea littoral [link in Turkish].

Sam Topalidis’ blog on Pontic Greek settlements on the southern Black Sea littoral.